Bullish Brew: The Case For A Multi-Year Coffee Rally ☕📈

A perfect storm for investors is brewing: Why a looming supply crisis and resilient consumer demand could send coffee prices to historic highs.

Summary

We believe coffee has 300-450% upside to $15-20/lb. The coffee market is supported by three key pillars: 1.) Critically low global inventories, 2.) Challenging production outlook, and 3.) Fairly inelastic consumer demand.

While concerns over a bumper crop in Brazil caused a pause in the recent bull market rally that started in 2024, the long-term bullish case for coffee remains hot.

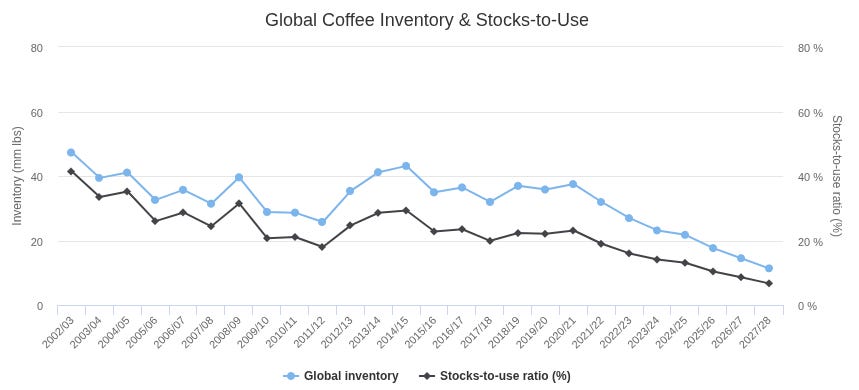

The world seems to be running out of coffee - global inventories will likely reach critically low levels during 4Q 2025 / 2026.

Introduction: Move Over Cocoa, Coffee Is The Real Jolt for Your Portfolio

Arabica coffee presents a powerful, long-term investment opportunity. We believe a new bull market began in 2024 will likely continue through 2030, with prices potentially reaching $15-20/lb, representing a 300-450% upside. This bull market is part of a larger “mega-cycle” that will likely reset the long-term nominal price range to $5-8/lb for the foreseeable future.

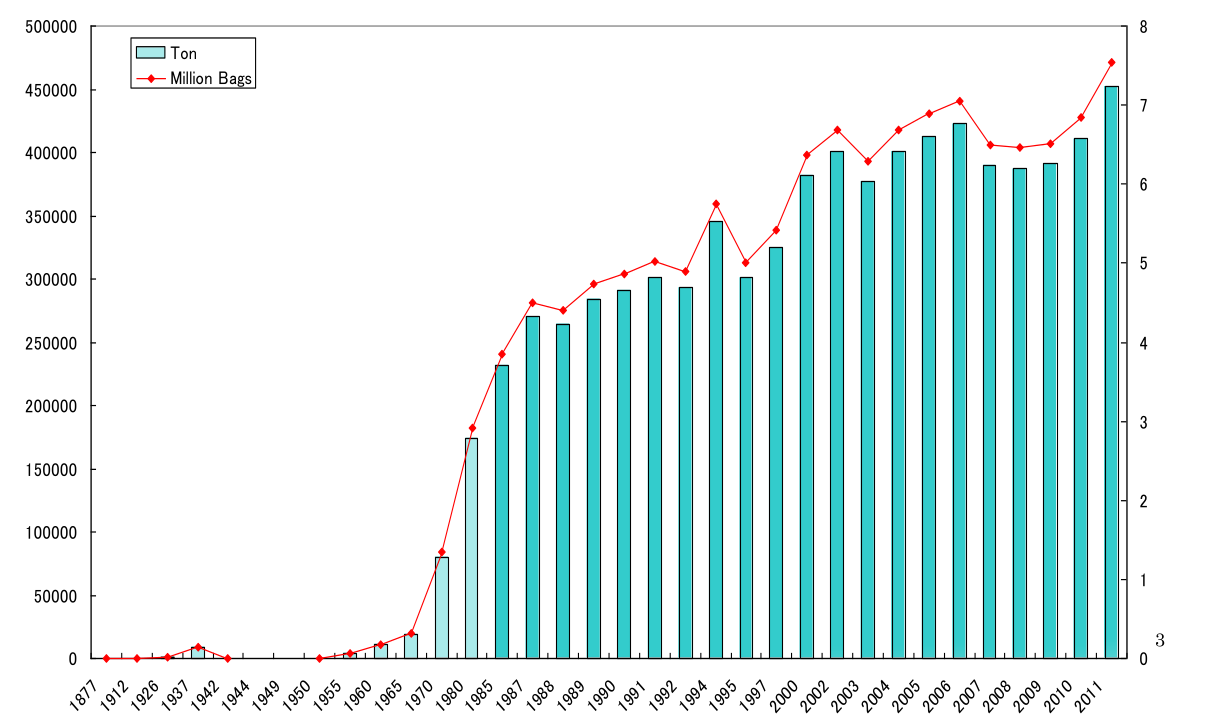

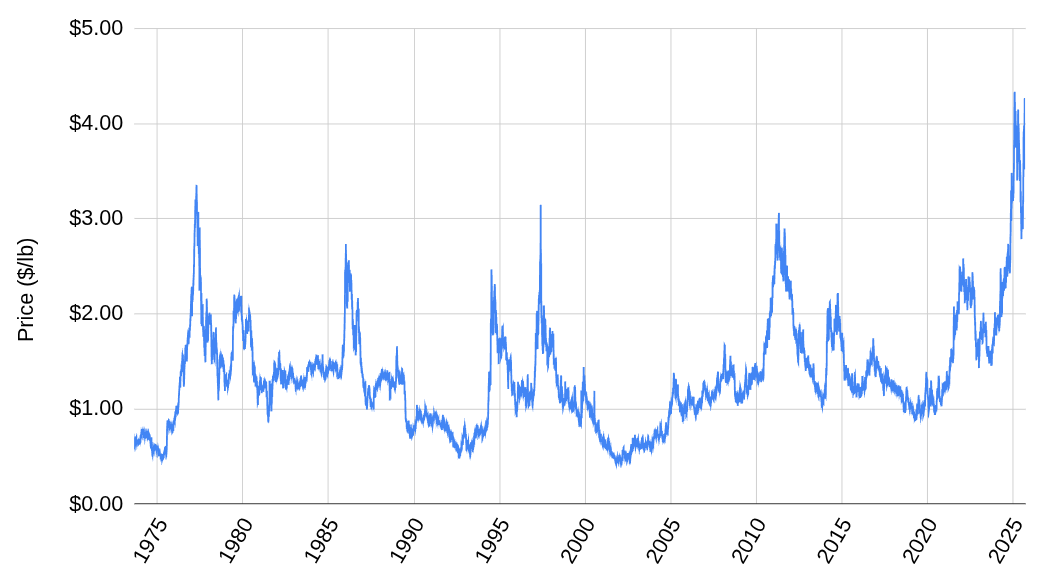

Coffee is one of the few commodities still trading significantly below its inflation-adjusted peak from 1977, which was approximately $3.50 ($18/lb inflation-adjusted). Given that current global inventories are even lower than they were in the 1970s, there’s a strong case for prices to surpass that historical peak.

For many, coffee is a daily ritual. For investors, it’s a dynamic commodity (the fifth-largest bulk export commodity by value according to Trade Data Monitor) often defined by price volatility.

Headlines during 1H 2025 focused on short-term headwinds from expectations of a large Brazilian crop that never materialized. More recently in September 2025, coffee experienced one of its largest sell-offs (~55 cents in a week, or 13%) on the rainfall forecast in Brazil’s coffee producing regions and news headlines stating two U.S. lawmakers are trying to modify tariffs on coffee. A deeper look reveals a compelling and well-supported long-term bullish thesis that should continue through 2030.

A Daily Necessity: Why Consumers Will Absorb Higher Prices

Coffee is more than a beverage - it is a daily supplement upon which many depend. Many coffee drinkers are dependent on the beverage for its natural caffeine boost, which translates to a daily coffee habit that can be tough to change. Coffee is one of few legal substances sold globally that people require and crave.

The daily cost of coffee beans for most coffee drinkers is relatively low compared to the perceived benefits received, which means that most coffee drinkers will place a high bid to maintain a continuous supply of their cherished drink.

Coffee tends to be fairly inelastic relative to other consumer goods. Industry analysts estimate the demand elasticity to be between 0.2 and 0.5 (a value of zero means consumers do not change their purchasing behavior when prices change, while a value of one means consumer will significantly change their demand given higher prices) - this means most consumers will likely continue paying up to buy coffee at higher prices.

A Critical Juncture: The Looming Supply Crisis

The world is running out of coffee. A multi-decade production deficit (demand has consistently exceeded supply) has led to a meaningful and sustained reduction of global inventories. We believe the market is now at a critical juncture where this depletion can no longer continue. As inventories hit dangerously low levels, prices will inevitably surge to incentivize new supply, a process that takes years since new coffee trees require 3-5 years to reach full productivity. This long delay in new supply suggests inventories will likely remain tight, making prices extremely volatile and sensitive to supply shocks for the foreseeable future.

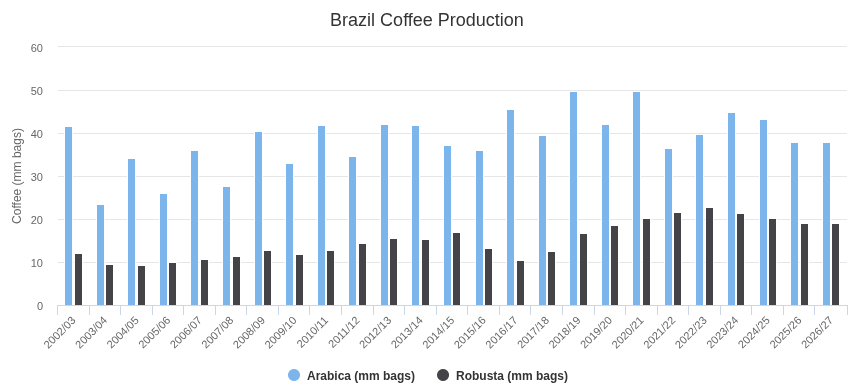

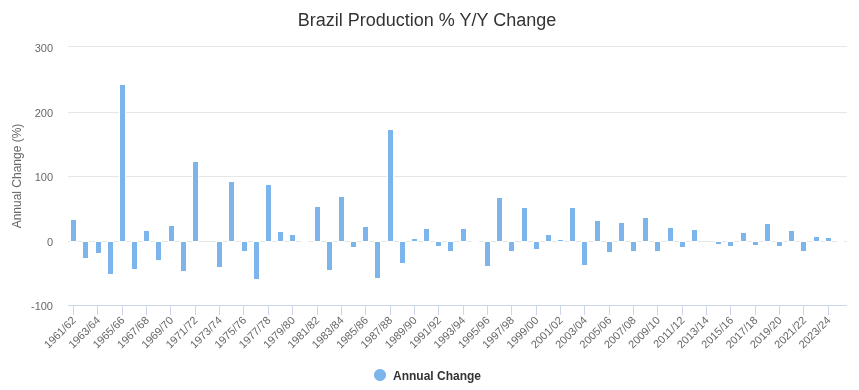

The forecast above assumes Brazil coffee production of 57m bags per year. It is important to note that any adverse weather events could have a sharp downward revision to supply. Brazil has a history of 40+% annual production drops following adverse weather events (a 40%+ annual drop occurred 8 times in the last 64 years).

Should we encounter another adverse weather event in any major coffee producing country, stocks-to-use could drop to low single digits quickly (an unprecedented level) and prices could skyrocket several hundred percent in a short time span.

We believe the outlook is positive for coffee prices absent any severe weather events. Should a material weather event occur, coffee prices could skyrocket quickly because the world no longer has a substantial inventory buffer to absorb supply shocks.

Global stock-to-use will likely drop below 10% (record low, which will put upward pressure on coffee prices) over the next few years if Brazil production remains below 60m bags per year. The average production in Brazil since 2010 has been 58.6m bags (per USDA figures). Over the last several years, the market has been overly optimistic each crop year, believing that Brazil could achieve close to its peak production of 70m bags reached in 2020/21.

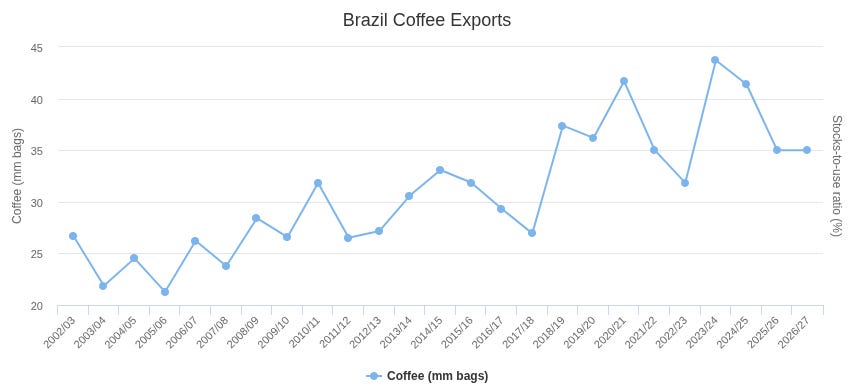

Many Brazilian industry experts and coffee analysts now believe that the run-rate for Brazilian coffee production will remain at or below 60m bags for the next several years due to structural shifts such as accumulated plant stress, weather, and farmer rotation to other more stable and profitable crops. More importantly, the level of Brazilian exports will likely drop to ~35m bags from a range of 40-45m bags over recent years due to a depleted domestic inventory - this means there will be much less coffee available for sale to importing countries like the U.S. and Europe.

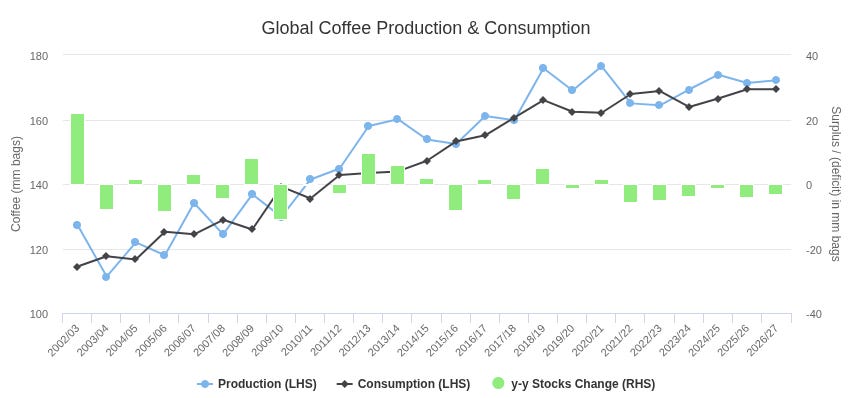

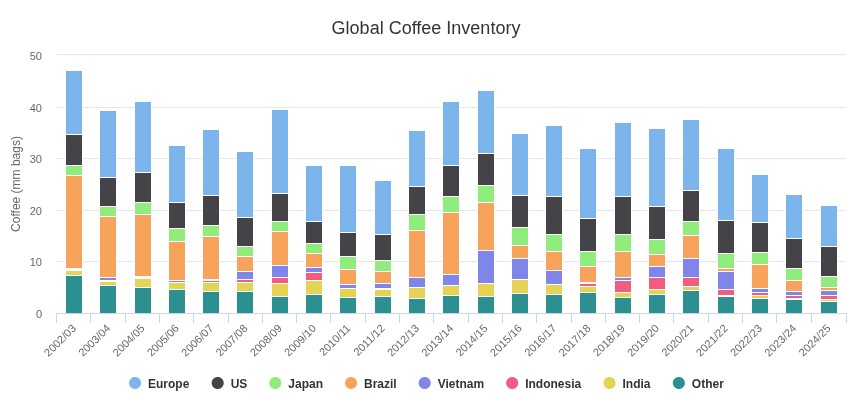

Global coffee inventory has dropped meaningfully over the last several decades years. Persistent deficits have led to a decline in global inventories. Key producing regions such as Brazil, Vietnam, and Indonesia have very low inventory relative to history.

Global coffee production has been below total effective consumption (reported consumption plus disappearance / unaccounted consumption; the green bars in the chart above show the ending stocks change which includes disappearance) for the majority of the years over the last several decades.

The Brewing Bull Market in Coffee

Coffee is one of the few commodities that is still meaningfully below its prior inflation-adjusted peak. Prior to the current bull market that started in 2024, the last nominal price peak was about $3.50/lb in 1977 (yes, it took almost 50 years to reach a new nominal price peak). The prior cycle inflation-adjusted peak was approximately $18/lb in 1977. The average inflation-adjusted price level for coffee during the 1970s and 1980s is above $5/lb.

Today, global inventories (both absolute inventory and inventory relative to consumption) are much lower than they were during the late 1970s cycle, which suggests that the price of coffee could possibly exceed the prior inflation-adjusted peak (higher than $18/lb).

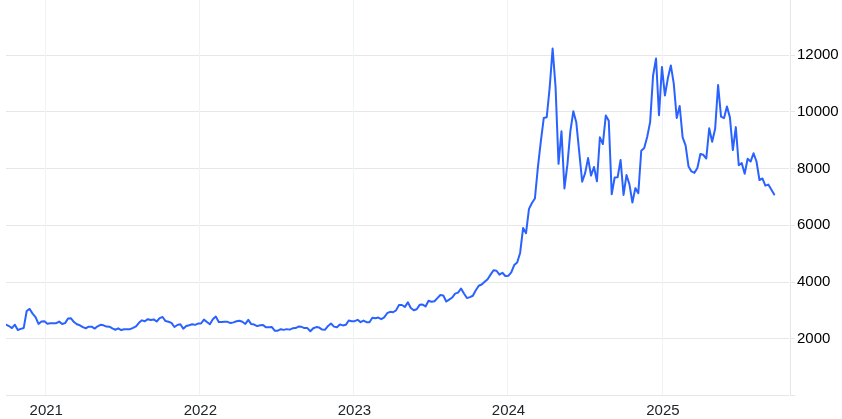

Long-Term Coffee Price (in nominal U.S. dollars)

A similar trade recently unfolded with cocoa. Between 2022 and 2024, cocoa prices soared about 500% due to similar factors that are bullish for coffee (a convergence of supply shocks and low inventory). Severe weather patterns driven by El Niño and climate change caused droughts, excessive heat, flooding, and unpredictable rainfall in West Africa, especially in Ivory Coast and Ghana, where most of the world’s cocoa is grown. While fundamentals remain positive for cocoa, we believe that coffee will quickly become the shining star in 4Q 2025 and 2026.

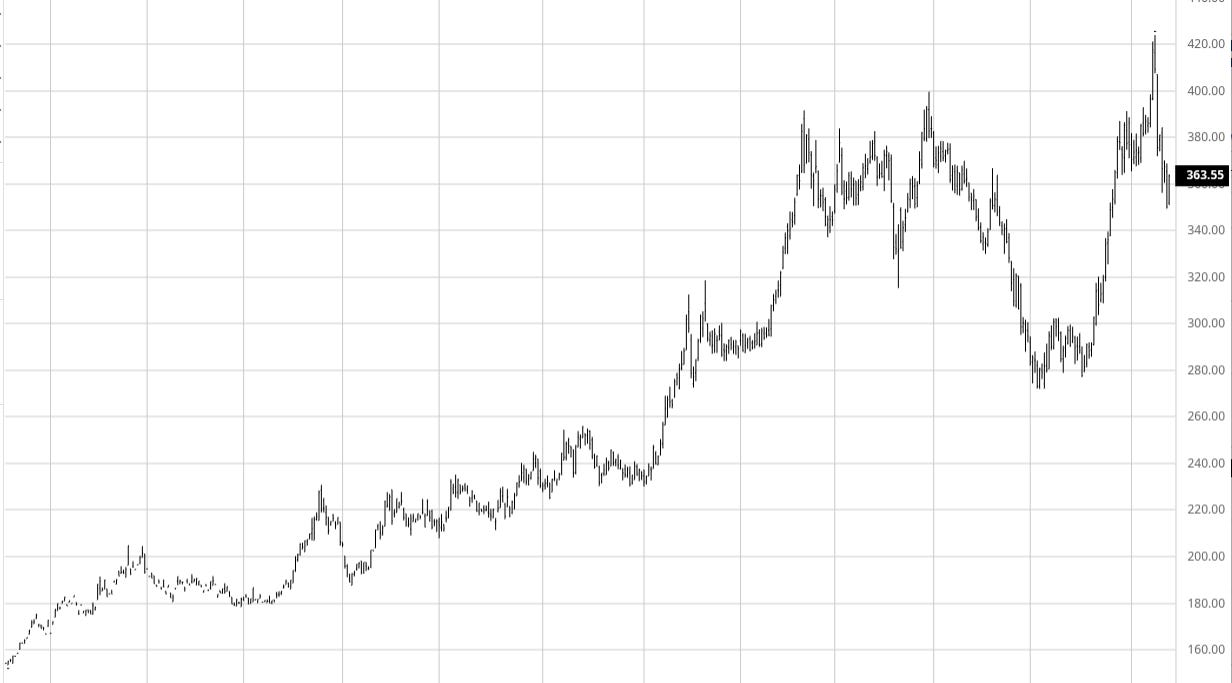

Cocoa prices (USD/ton)

The coffee market goes through bull and bear cycles driven by a combination of factors such as weather events, geopolitical volatility, and changing demand trends. The most famous and dramatic bull market occurred in mid/late 1970s, triggered primarily by a catastrophic “Black Frost” in Brazil in July 1975 that wiped out a significant portion of the country’s coffee crop.

Brazil was (and still is) the world’s largest coffee producer. The Black Frost caused a massive supply shock for the entire world. Prices skyrocketed, leading to the nominal peak of about $3.50/lb in 1977 (inflation-adjusted price of $18/lb today), a nominal price price not surpassed until the recent bull run almost 50 years later.

Today, global coffee inventories are declining and global production is plateauing. Increased volatility in weather patterns in key coffee producing regions such as Brazil is challenging the production outlook. Many coffee farmers are fatigued after years of struggling to get by, so they have chosen to rotate to other more profitable crops less prone to volatility.

A Fundamental Imbalance: Volatile Supply vs. Stable Demand

The coffee market is characterized by a fundamental and persistent imbalance between supply and demand dynamics. On the demand side, global consumption of coffee is relatively stable and grows at a rate of about 2% annually.

Consumption growth is driven by rising disposable incomes and the proliferation of coffee culture in emerging markets, particularly in Asia. For most consumers, coffee is a daily habit, and consumption patterns are not highly sensitive to short-term price fluctuations.

Coffee production is notoriously volatile and subject to a wide range of unpredictable factors. Coffee’s production is dependent on weather conditions, and adverse weather events, such as frosts, droughts, or excessive rainfall, can severely damage crops and cause production to fall sharply.

This dynamic creates a market that is highly susceptible to supply shocks. When a significant weather event occurs in a major producing country, the stable, growing demand quickly outstrips the volatile, suddenly-reduced supply.

The fundamental nature of the coffee market, with its stable demand base and inherently volatile supply, suggests that periods of low inventory and production challenges are likely to be followed by a significant bull market (similar to what happened recently with cocoa).

This supply-demand imbalance can lead to rapid and dramatic price spikes, as seen in prior coffee cycles:

1975-1977 (+725%)

1978-1979 (+185%)

1985-1986 (+208%)

1993-1994 (+473%)

1996-1997 (+305%)

2009-2011 (+242%)

2013-2014 (+219%)

2020-2022 (+251%)

2024-?

Coffee is still below its inflation-adjusted median price range of the 1970s and 1980s. We believe that we are in the midst of a mega-cycle shift whereby the coffee price range will reprice higher structurally. Coffee traded in a fairly consistent nominal price range (~$1-3/lb) for about 50 years, and we think the new range will higher adjust soon given accumulated inflation and low global inventories.

We think the market requires a large price surge to $10+/lb to wake up the world and incentivize farmers to become aggressive in planting coffee (similar to what we are seeing in cocoa now following the price increase).

Even if farmers start planting more coffee tomorrow, it will take 3-5 years for those new coffee trees to reach full productivity (cocoa trees can take 5-10 years to reach full productivity). Typically the length of the time required to introduce new commodity supply determines how long the bull market can last when global inventories are depleted (for example, the time required for new chicken egg supply is considerably faster than the time required for a new gold mine).

Coffee farmers in many emerging market coffee producing regions are undercapitalized and have high costs of financing. Decades of depressed prices and countless bankruptcies have left the industry stressed and reluctant to make a big bet on sustained higher prices. Banks in many Latin American countries often charge coffee growers double-digit interest rates, which is a high cost of capital and can be prohibitive for new investment.

Brazil’s Harvest: Why the World’s Cup is Running Dry

Brazil is the world’s leading coffee producer and exporter, making its production a critical determinant of global coffee supply and prices. The sheer volume of Brazilian coffee, which accounts for approximately 35-40% of the world’s total output, means that fluctuations in its harvest - whether due to adverse weather like drought or frost - have immediate and significant ripple effects across the international market.

The country’s influence is further amplified by its capacity to produce both Arabica and Robusta beans. Brazil is able to serve a broad spectrum of global demand, from high-quality specialty coffees to large-scale commodity blends. The state of Brazil’s coffee industry is a crucial barometer for the stability and direction of the entire global coffee market.

Recent Brazil Field Report

Maja Wallengren (@SpillingTheBean https://x.com/SpillingTheBean), a veteran coffee analyst for more than 30 years, recently completed her second Brazilian crop tour this year. Maja’s takeaways from country-wide trip found that:

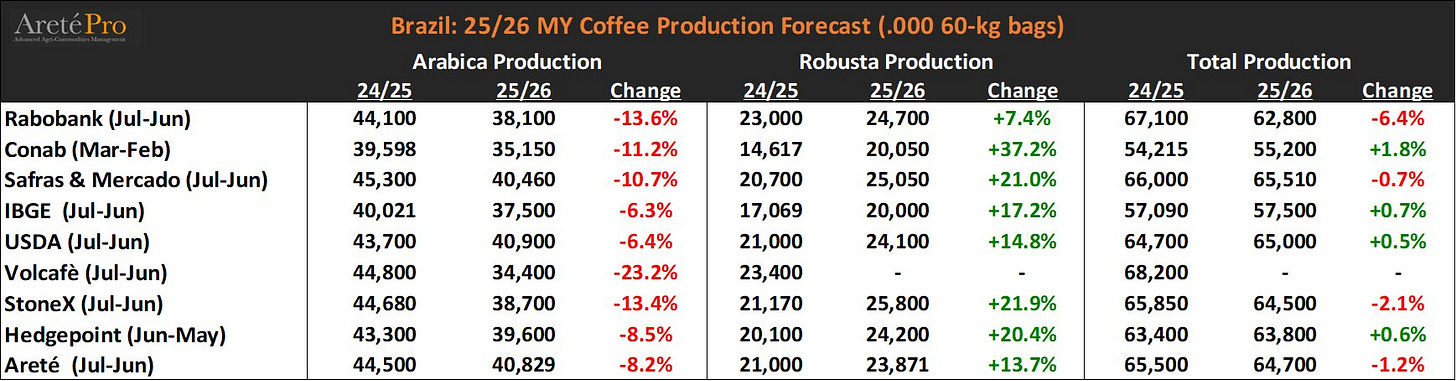

Brazil’s coffee production of Arabica and Robusta beans will likely be lower than USDA, CONAB, and other industry forecasts. She believes the low production will persist the structural deficit (more demand vs supply of coffee) for at minimum two years (she believes it could persist through 2030).

Brazil’s domestic inventory is very low. Maja reported major exporter warehouses were running at 10-20% capacity at this time of the harvest vs full in prior years (see photos here).

The Brazilian government recently called on producers to supply the domestic coffee market as a priority over exports - this is a sign that domestic Brazilian supply is running tight. Brazilians consume a lot of coffee for the domestic market (~22m bags, or about 35% of production). Brazilian domestic inventories are very low (estimated to be under 0.5m bags, down from 17.9m bags in 2002/03).

Pronounced frost in August 2025 and heat wave in September 2025 will affect the coffee bean yields in 2025/26. Accumulated stress on the coffee trees affects the yield (productivity) of coffee trees for many crop cycles - it will take at minimum a couple years for the trees to recover from stressful weather.

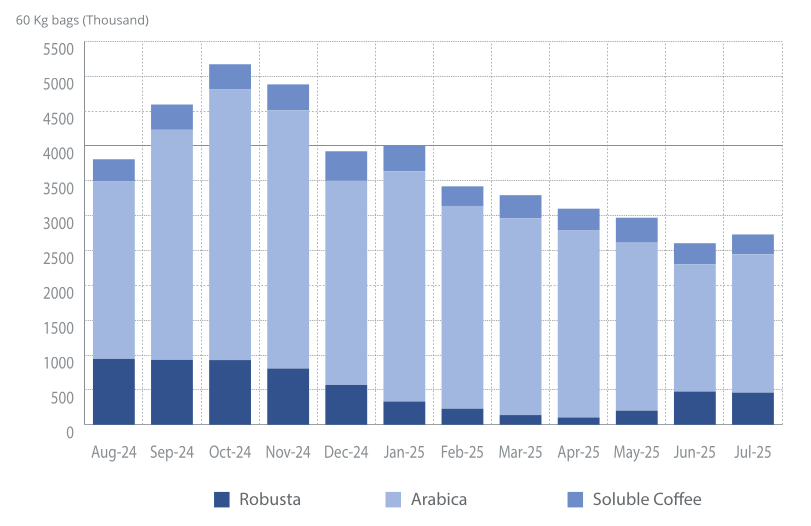

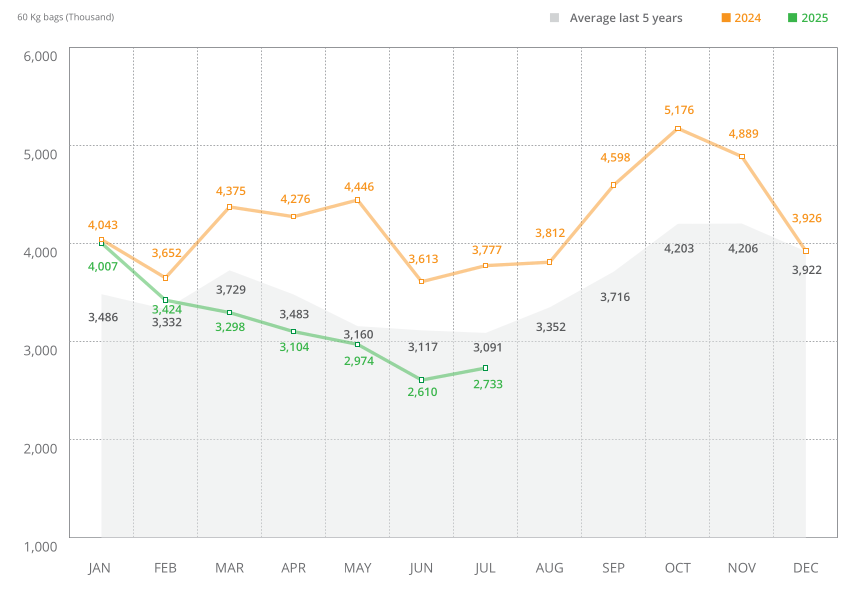

Brazilian Exports

Cecafé noted a major decline in the volume of coffee bean exports YTD through August 2025 as total shipments fell by 21% compared to the same period in 2024 (Arabica down 13% YTD and Robusta down 58% YTD). This drop in volume reflects the ongoing impact of weather-related production challenges and depleted inventories, which have left the world’s largest coffee producer with less supply to ship to international markets. View Brazil export data here.

Brazilian Coffee Monthly Exports

Brazil coffee exports have declined y/y through most of calendar year 2025.

Brazil exported 40m+ bags (per Cecafé) for several years (2020/21, 2023/2024, and 2024/25), and the market began to expect that 40m+ bags for export was sustainable. We believe this is an example of how market participants tend to extrapolate linear trends (”up and to the right” in this case). Typically the market adjusts when a trend extrapolation changes, as we believe is happening now with Brazilian coffee production.

We believe the future export capability of Brazil will likely be at or below 35m bags for the next several years given production challenges and very low Brazilian inventory. Part of the elevated exports were driven by a depletion of domestic Brazilian inventory (Brazil had 5m bags in inventory in 2021/22, and now it’s now estimated to be under 0.5m bags). The reduction in annual Brazilian exports removes 5-8m bags of coffee available for sale to the world relative to recent years.

The international price of coffee is based on “supply available for export” rather than global production, since exports are representative of inventory available for purchase. Brazil and other major coffee producing regions are running low domestic inventories, which means less coffee will be available for export relative to prior years.

Brazil experienced elevated production for several years since 2018/19. We believe the normalized run-rate production is lower than recent history given weather challenges, plant stress, and farmer rotation to other more sustainable and profitable crops. The maximum production was 70m bags in 2020/21. We believe the market will stabilize in 55-60m bag range for the next several years at “full production”.

Full production is the maximum possible production in any given crop year - think of it as a “starting point” and the final production quantity is anywhere between zero and that amount. Full production is a function of area planted and productivity of the crop (yield). Adverse weather events (drought, excessive rain, heat waves, frost, hail, etc.) revise down the full production quantity. Production varies year to year based on several factors: area planted, productivity and weather.

Significant weather events (frost, drought, etc) could haircut Brazilian production quickly. Since 1961 (64 years), there have been 8 weather events that caused a 40% or greater annual decline in Brazilian production. This means that approximate every 1 in 8 years Brazil experienced a 40%+ annual decline in coffee production. The last 40%+ decline was 30 years ago (1995/96 crop year).

Many analysts have cut their estimates for the Brazilian coffee production. There is risk for further cuts to the downside based on recent field reports. We believe 2025/26 numbers still need to fall more. Risks to the 2025/26 crop include:

Frost: Frost impacted several important Brazilian coffee regions in August 2025. Coffee trees with frost damage have significantly reduced productivity (in many cases it drops to zero production) because the tree loses its leaves and must spend its energy to re-grow leaves before it can re-grow flowers that turn into coffee fruit.

Heatwaves and hail: September 2025 experienced a lot of weather volatility including hail and heatwaves above 40 degrees Celsius in several important Brazilian coffee regions. Excessive heat also negatively affects coffee tree productivity (the tree will often end up aborting flowers that are required to produce the coffee fruit). Arabica coffee trees are extremely sensitive to weather volatility.

Future weather risk: Continued weather risks exist through 4Q 2025 and 1H 2026. Flowering coffee trees are particularly sensitive and can abort the fruit given stress. Also, the maturing fruit can be damaged during prolonged drought. We believe the theoretical maximum production for the current crop year (2025/26) is about 55-60m bags. Further weather risks could lower this production forecast.

Brazilian coffee production data can vary by source (USDA, CONAB, etc). Estimates for Brazil have been revised down for 2024/25 and 2025/26. We believe that estimates will continue to be revised down given persistent weather issues and accumulated plant stress.

Coffee Crop Year

Coffee statistics are usually reported as a crop year (also called marketing year), rather than a calendar year. The crop year is used to measure the harvest of a particular agricultural commodity from one season to the next (ie a single growing cycle). The crop year depends on the country’s geographic location. In Brazil, the USDA uses a crop year from July until June the following year.

Typical stages of a crop year in Brazil include:

Flowering: (September-October) The first major rains trigger the flowering of the coffee trees. This stage is highly sensitive - inadequate rain or high heat can reduce the fruit set. The abundance and uniformity of the flowering is a critical factor for crop yield. The flowers are small, white, and fragrant. The flowers typically last only for a few days before giving way to the initial stage of the coffee cherry.

Fruit set and pinhead stage: (October-November) After flowering tiny green “pinhead” cherries form. The coffee trees require stable moisture and mild temperatures to support fruit retention. Excessive precipitation can cause issues.

Fruit development: (December-February) The coffee beans grow rapidly inside of the cherry. Typically this occurs in the rainy season, which supports bean growth. Excessive rain or humidity can increase the risk of diseases (ie coffee leaf rust).

Bean filling and maturation: (March-April) The coffee beans gain weight and harden. Cherries start to turn color from green to yellow or red depending on the variety. Drier weather is required - excessive rain can lower quality. Droughts can prevent the bean from gaining sufficient weight.

Harvest: (May-August) Farmers harvest the coffee cherries at peak ripeness. Sometimes weather volatility can cause the crop to ripen at different times, which lowers the yield because farmers cannot collect all of the cherries in a single pass.

Currently we are entering the flowering stage for the 2025/26 crop year in Brazil. Field reports in August 2025 suggest that many of the coffee trees were negatively impacted by frost, causing the trees to loose their green leaves (the leaves turn brown and then fall off).

When a coffee tree does not have any leaves it typically devotes most of energy to regenerate the leaves first, before making any effort to flower (required to produce a coffee cherry). Trees that lose most of their leaves have a significant reduction in their cherry production (typically close to zero). Coffee trees focus first on survival, then on reproduction. A tree without leaves is unable to collect solar energy, so it must focus on regrowing its leaves first to survive.

U.S. tariffs on Coffee

The new 50% U.S. tariff on Brazilian imports has further disrupted the global coffee market by making Brazilian coffee more expensive for American importers, causing them to seek alternative sources. While recent news suggests that two U.S. lawmakers are seeking to modify these tariffs, our core thesis does not hinge on this.

Any changes to the tariffs would likely cause only a short-term pullback, and it would not impact our long-term price targets. The primary driver remains critically low global inventories and plateauing production. It’s notable that coffee prices haven’t seen the dramatic swings around tariff announcements that other commodities like copper or orange juice have.

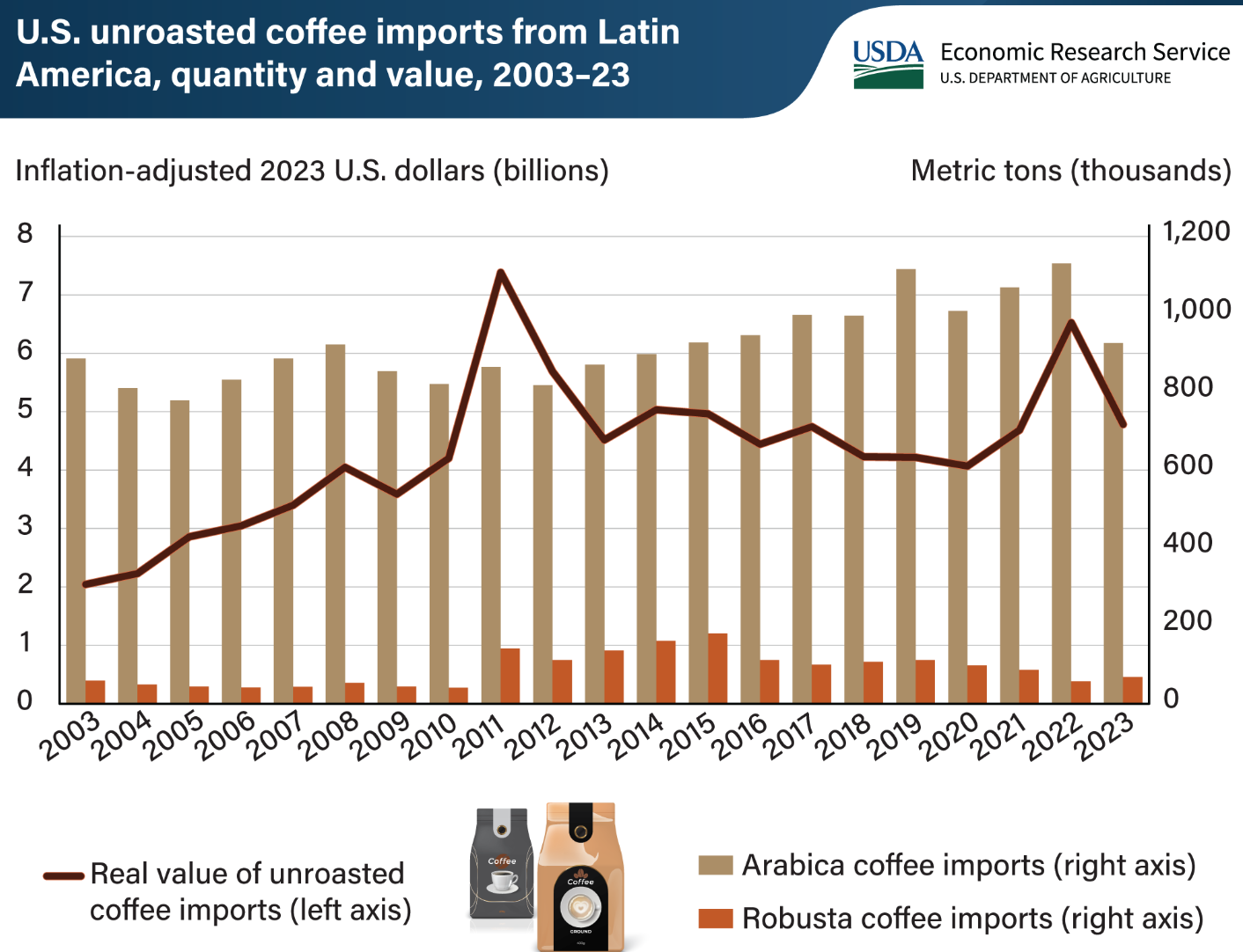

The US consumes about 25m 60kg bags of coffee each year (view data here) and it imports the vast majority of this coffee (Hawaii is a small producer of premium coffee). Historically, more than 90% of U.S. imports have been the Arabica variety, due U.S. consumer preference of the better flavor profile and quality of Arabica beans.

Current U.S. tariffs on large coffee producing countries in Latin America include:

Brazil 50% tariff (~35% of U.S. imports)

Colombia 20% tariff (~27% of U.S. imports)

Honduras 10% tariff

Coffee traded down intraday approximately 5% when it was announced that two U.S. lawmakers were pursuing a tariff modification. We believe that this move erased a significant amount of the tariff impact baked into coffee prices.

Market Opportunities in China

China still remains a huge potential market that is not developed fully. Some analysts think China could experience a rapid growth in consumer adoption similar to that which Japan experienced during its economic boom in the 1980s. Luckin Coffee (LKNCY), a Chinese coffee chain, is aggressively growing its footprint in China and the broader world.

Japan Coffee Imports

1. Critically Low Global Inventories

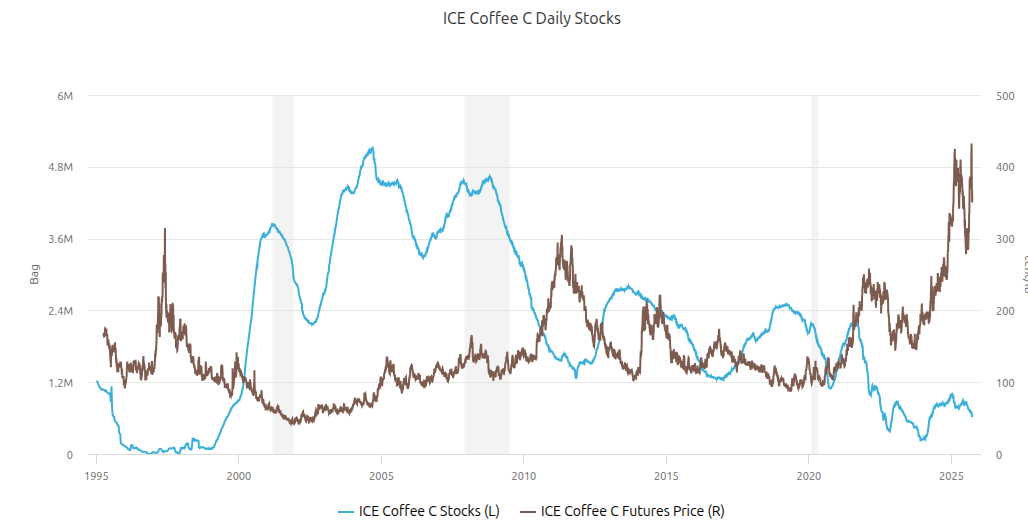

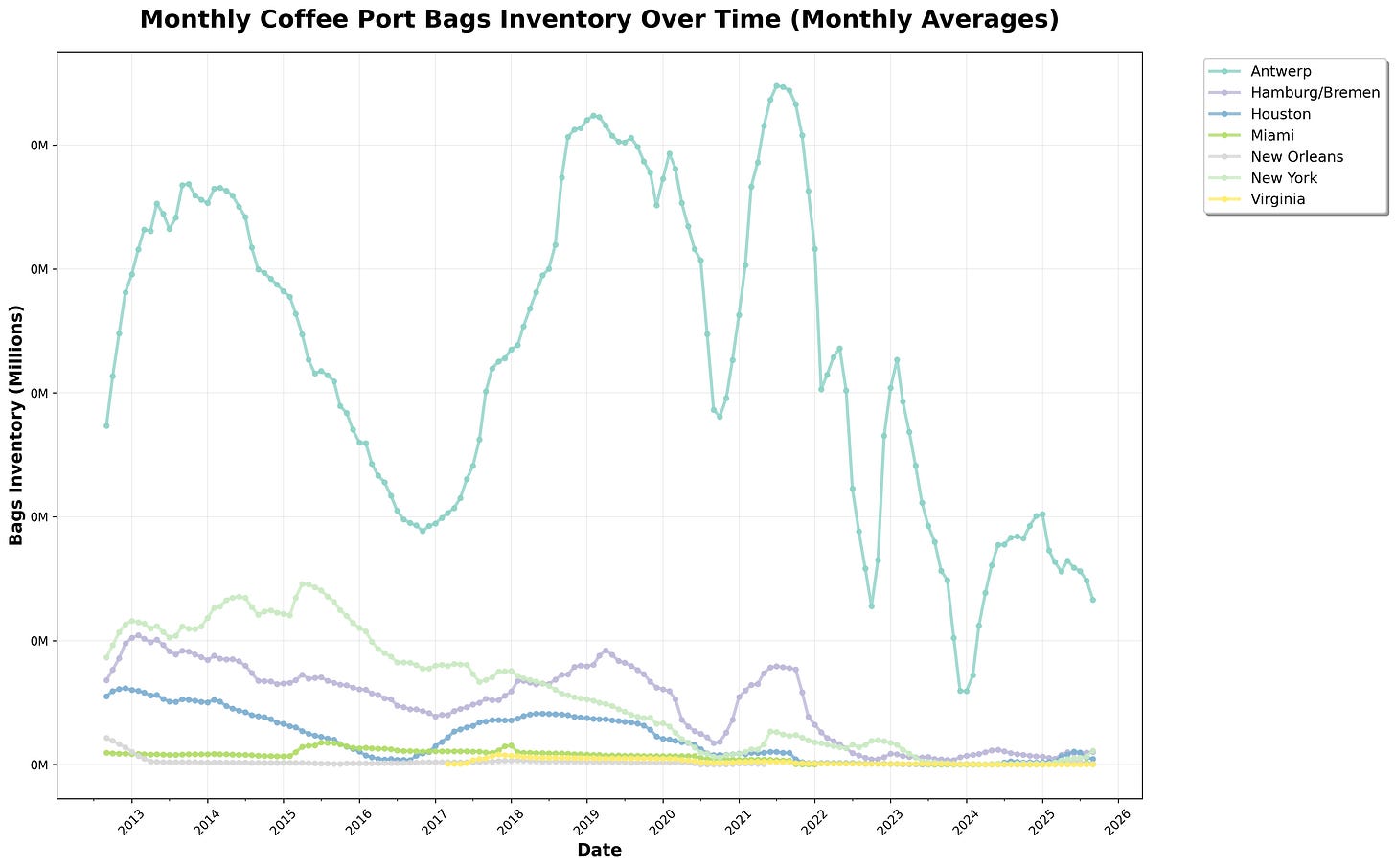

The current state of low global inventories the most significant immediate driver of the bullish thesis. Exchange-monitored coffee stocks are at low levels, providing a strong floor for prices and creating a tight supply environment.

ICE and USDA coffee stocks serve different purposes and measure different metrics. ICE stocks are a specific, high-frequency dataset that tracks the amount of coffee certified for delivery against the global futures contract, making it an important indicator for traders and the financial market (ICE stocks are a real-time snapshot of the highest-quality, exchange-approved coffee available for purchase by anyone in the world). USDA stocks provide a broader, more fundamental view including stocks held at ports and warehouses not available for purchase.

Global inventories are declining:

World inventory: USDA FAS reported global inventories relative to consumption (stocks-to-use) are at multi-decade lows (lowest level in 25+ years). We estimate that global inventory will continue to drop through at least 2028 as the structural deficit continues. We believe that stocks-to-use ratio could decline to critical levels which would cause strong pressure on coffee roasters and retailers to buy at any cost to secure supply.

Arabica ICE inventories: ICE Arabica inventories are just 660,000 bags - typically the market is considered tight when inventories are below 1m bags. ICE inventories begun dropping again in August/September 2025 as purchasers take delivery of coffee inventories.

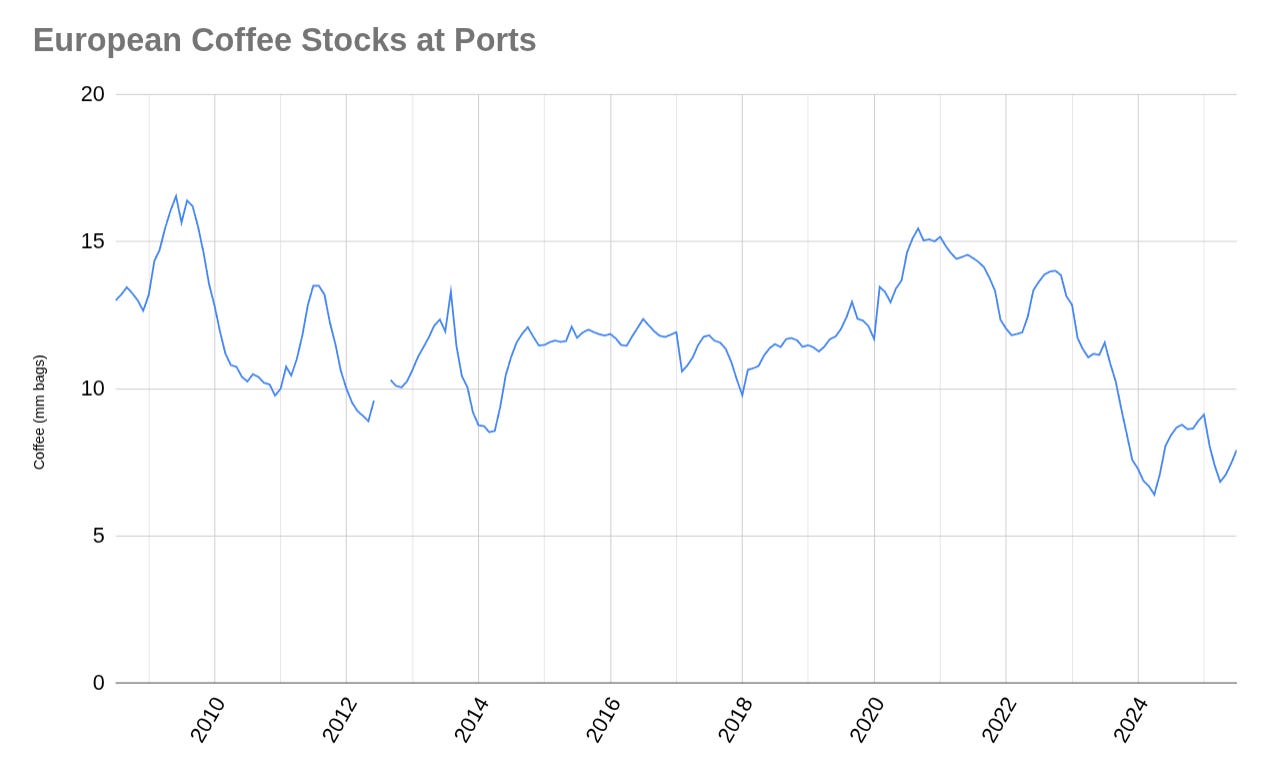

European inventory: The European Coffee Federation reported that inventories are at ~8m bags (474,966 tons) as of June 2025, down from ~14m bags (840,000 tons) in 2022.

Europe historically stored 10-15m coffee bags at port warehouses. Starting in 2022, the European port inventory declined to 7-8mm coffee bags. We believe that inventory could decline further given lower Brazilian exports over the next couple years.

The adoption of Just-In-Time (JIT) inventory management has left the market with minimal buffer stock. The coffee market’s previous attempt at JIT in 1997 coincided with the El Niño event, which created a massive supply shock and caused prices to skyrocket about 300%. This vulnerability has reappeared, making the market highly susceptible to disruptions and price volatility.

Supply-side pressure combined with strong global demand could create a powerful upward force on prices.

2. Challenging Production Outlook

The long-term supply outlook remains challenging, supporting the continued bullish narrative. During Maja Wallengren’s recent interview with Cooxupe Cooperative (largest Brazilian coffee exporter with approximately 11% of total export market share), President Augusto Rodrigues de Melo stated:

Production Decline: The 2025 coffee harvest in Brazil, specifically in the Minas Gerais and Cochupé areas, is “much smaller” than expected. Augusto Rodrigues de Melo noted that with 88% of the harvest completed (as of mid/late August 2025), there is a noticeable decline, and the projected target for the season may not be met.

Weather as a Primary Factor: A significant cause of the reduced production is adverse weather conditions. The conversation highlighted five consecutive years of poor weather, including dry spells, lack of rain, hailstorms, intense cold, and hotter temperatures, all of which have negatively impacted crop productivity.

Reduced Productivity: Augusto Rodrigues de Melo emphasized a multi-year trend of falling productivity since 2020, despite producers’ efforts to increase cultural practices to boost production. The accumulated energy for the crops is low, and the trees are not able to recover from the stress.

Market Impact and Price Increase: The decline in production has led to a rise in market prices. Augusto Rodrigues de Melo explained that this is a direct result of supply and demand, as there is less coffee available to meet global needs.

Zero Stocks: Coffee stocks are “zero.” The inventory from previous years has been used up, and the current harvest is not for stocking but for immediate customer shipment, creating a tight supply situation. This means that it is unlikely ICE stocks and other exchange warehouses will likely continue to face inventory drawdowns.

Future Outlook: The outlook for the 2025/26 harvest is cautious. While it may be slightly better than the current one, it is not expected to be a record or super harvest like in 2020/21. The climate continues to be a major concern, and the long-term health of the crops is at risk.

Arabica beans, which are used for most specialty coffee, are particularly vulnerable given a variety of factors. Arabica coffee is very sensitive to weather extremes, and key growing regions in Brazil and Colombia have faced recurring droughts and heavy rains that disrupt the biennial production cycle.

The threat of climate change looms overhangs the current production footprint - some projections suggest that up to 50% of the land suitable for Arabica coffee cultivation could be lost by 2050.

Photos above are from Maja Wallengren’s recent August 2025 trip to Brazil coffee producing regions. She noted many of the regions were severely damaged by frost, which is indicated by brown leaves. The trees with brown leaves are typically unable to produce coffee beans during the next harvest.

3. Fairly Inelastic Consumer Demand

Coffee demand is remarkably resilience even in the face of rising prices, given many people highly value the drink for its taste and productivity boost. The demand for coffee is considered to be relatively “inelastic” (estimates range from 0.2-0.5) meaning price changes are often absorbed by the consumer rather than affecting the quantity consumed.

A combination of robust demand and critically low global inventories could create a perfect storm for sustained high prices. As with other commodities and consumer goods, a perceived scarcity of inventory (future shortages) may exacerbate the price move upward as the supply chain and roasters and consumers rush to build their own private inventories by hoarding supply. This phenomenon often occurs in cyclical industries where there are perceived shortages on the horizon.

Anticipatory buying will further reduce available supply and contribute to elevated demand over the coming years, thus potentially creating a self-reinforcing cycle of high prices that could persist until global production can catch up and inventories are fully restocked to normal, historical levels (we estimate 2030 at the earliest).

Key Risks to the Bullish Thesis

No investment is without risk, and coffee is no exception. For our bullish thesis, it is important to consider the potential factors that could cause coffee prices to fall.

Larger than expected production: Exceptionally good weather in major producing regions, particularly Brazil and Vietnam, could lead to an oversupply of coffee beans. A supply surplus can put downward pressure on prices as producers and traders compete to sell off excess stock. Recent industry commentary suggests that this risk is lower through the next year.

Speculative Unwinding: If investors begin to unwind their long positions, it could trigger a sharp and rapid decline in futures prices, regardless of underlying supply and demand fundamentals. Currently speculative long interest is fairly muted (traders are not too long or short relative to history).

U.S. Tariff Repeal: Coffee may sell-off on a reduction or elimination of Brazilian tariffs on coffee. While we believe this is more headline risk than anything, it could cause a short-term pullback. It is important to note that coffee prices did not rise dramatically when tariffs were announced and implemented. Other commodities such as orange juice and copper experienced more pronounced buying and selling around tariff announcements.

Coffee Stocks

While we recommend owning coffee futures (KC1) as the best way to play the bull market, investors can also short coffee-exposed equities as fears build over rising input costs. We believe most of these companies will ultimately be able to pass along the input cost to consumers, and the dramatic rise in coffee prices might actually enable coffee chains to increase prices more than their costs resulting in higher margins (consumers who see headlines stating coffee bean prices have risen ~500% will be more understanding of a retail price increase).

Coffee beans are actually a fairly low input cost relative to the retail price of a coffee cup at Starbucks. An 8-oz cup of coffee uses about 10 grams of ground beans (roughly 0.35 ounces). Since a pound of roasted coffee has 16 ounces, at $4 per pound the cost per ounce is $0.25. Multiplying 0.35 ounces by $0.25 gives about $0.09, meaning the actual coffee in the cup costs less than $0.10; the rest of the retail price comes from milk, sugar, cups, labor, and overhead rather than the beans themselves. Even at $20/lb, the coffee beans cost would be $0.50 per cup, which is a difference of $0.40. Most coffee chains will likely be able to pass along this cost to consumers - especially as consumers read headlines about coffee bean prices increasing ~500% since the bull market began.

Starbucks (SBUX)

As the world’s largest coffee chain, Starbucks is heavily exposed to coffee bean costs, which represent a core input in its business model. Starbucks uses hedging strategies to smooth near-term price volatility, a five-fold increase in coffee prices would overwhelm those measures and put significant pressure on margins. Starbucks does have strong brand loyalty and pricing power, but pushing through drastic price increases risks consumer pushback, lower transaction volumes, and slower international growth. The result would likely be compressed profitability short-term and weaker same-store sales momentum.

J.M. Smucker Company (SJM)

J.M. Smucker has a significant retail coffee portfolio, including brands such as Folgers, Dunkin’ At Home, and Café Bustelo. Unlike coffee shop chains like Starbucks, Smucker’s business is centered on selling packaged products for at-home consumption. The company is still exposed to fluctuations in green coffee bean costs, which are a key input. Smucker uses commodity hedging to manage their green coffee cost volatility, but a sharp and sustained price increase would necessitate price hikes to consumers. J.M. Smucker management noted during their summer 2025 earnings call that the company plans to take additional pricing actions to recover green coffee costs. Management is estimating a consumer elasticity of 0.5, which means price increases will likely be absorbed by consumers.

Keurig Dr Pepper (KDP)

Keurig Dr Pepper has a significant presence in the coffee market, primarily through its Keurig brewing systems and coffee pod brands like Green Mountain Coffee Roasters. KDP’s revenue is largely derived from the sale of brewers and single-serve pods for at-home and office consumption.

Keurig Dr Pepper is exposed to green coffee bean cost fluctuations, as these are a major input for its coffee pods. KDP historically used pricing actions and commodity hedging to mitigate the impact of rising costs. In recent earnings calls, KDP management has indicated that its strong brand portfolio and the convenience of its brewing system allow for some pricing power, suggesting that consumer elasticity for their products is relatively low.

Nestle (NSRGY)

Nestlé is the world’s largest food and beverage company and has a vast and diversified portfolio, with coffee as a major pillar. Nestlé’s brands include Nescafé and Nespresso. It also has a partnership with Starbucks established 5 years ago under the Global Coffee Alliance which enables Nestlé to leverage its distribution footprint for Starbucks coffee. During Nestlé’s summer 2025 earnings call, management noted a lower elasticity for coffee products, indicating that consumers were less sensitive to recent price increases than in other categories.

Nestlé management stated that “margins of Coffee and Confectionery will get worse before they get better” in the second half of the year due to a “delayed impact of higher input costs,” including a potential “increased tariff impact.” A prolonged and steep rise in green coffee costs could pressure profit margins.

Dutch Bros (BROS)

Dutch Bros, a fast-growing U.S. drive-thru coffee chain, lacks the global scale and diversified product mix of Starbucks, leaving it more vulnerable to a coffee price shock. The company is still in its rapid expansion phase, relying on affordable drinks and customer volume to fuel growth. With limited pricing flexibility and thinner brand equity compared to Starbucks, Dutch Bros could face margin erosion and a potential slowdown in unit economics if raw coffee costs surged, making it particularly sensitive to such a commodity shock.

Luckin Coffee (LKNCY)

Luckin Coffee has become a major player in China’s coffee market, competing aggressively with Starbucks by offering low-cost drinks and rapid digital ordering. Its business model depends on high volume and thin margins, which makes it especially exposed to swings in coffee bean prices. A sharp spike in coffee costs would hit profitability hard and could destabilize its growth trajectory in China’s price-sensitive consumer base.

Conclusion: The Brew Is Ready To Pop

We believe the foundation for a historic, multi-year coffee bull market is firmly in place. We think that coffee will be one of the better performing assets as the price of coffee increases 350-400% to $15-20/lb during the current bull market. The convergence of a structural supply deficit, challenging production outlooks in key producing regions, and a consumer base that shows a remarkable willingness to pay more, creates a powerful and sustained upward force on prices. We believe the market will begin to realize the gravity of the inventory situation in 4Q 2025 and 1H 2026.

We believe this bull market will follow the path of cocoa, leading to a significant repricing of the commodity to reflect the new supply-and-demand reality. While the market may face short-term pullbacks, the path of least resistance is up. This trend can be played directly through futures or by carefully trading equities. As the world wakes up to this reality, we believe that coffee will be more than just a morning ritual; it will be one of the more profitable commodity trades in the coming years.

Disclaimer and Disclosure: We have a financial interest in the coffee market, as we hold a long position in coffee through various instruments. Please remember that this post is for educational and entertainment purposes only and should not be considered investment advice. Investing involves risk, and past performance is not indicative of future results. We are not a licensed financial advisor, broker, or investment professional.